If you’ve ever looked at a tin of high-end Chinese green tea and wondered why some leaves cost more than a fine bottle of champagne, the answer usually lies in two words: The Harvest.

In the world of Chinese tea (Cha), harvesting is an art of timing and anatomy. For amateurs, understanding these nuances is the “secret handshake” that helps you navigate tea shops with confidence. Let’s break down how the when and the what determine the soul of your brew.

1. Timing: The Race Against the Calendar

In China, the tea harvest is dictated by the 24 Solar Terms of the traditional lunar calendar. The most prestigious teas are harvested in early spring when the plant is just waking up from winter dormancy.

Ming-Qian (Pre-Qingming)

- The Window: Harvested before the Qingming Festival (usually April 4th or 5th).

- The Profile: These are the “First Flush” teas. Because the weather is still cool, the tea bushes grow slowly, concentrating amino acids (which provide sweetness and umami) and keeping tannins (bitterness) low.

- The Grade: This is the highest grade. The yields are tiny, making these teas rare and expensive.

Yu-Qian (Pre-Rain)

- The Window: Harvested after Qingming but before the Guyu (“Grain Rain”) festival (around April 20th).

- The Profile: As the weather warms, the leaves grow faster. These teas have a more robust, “green” flavor and a stronger body than Ming-Qian teas.

- The Grade: High to Mid-grade. Many tea connoisseurs actually prefer Yu-Qian because it stands up better to multiple infusions.

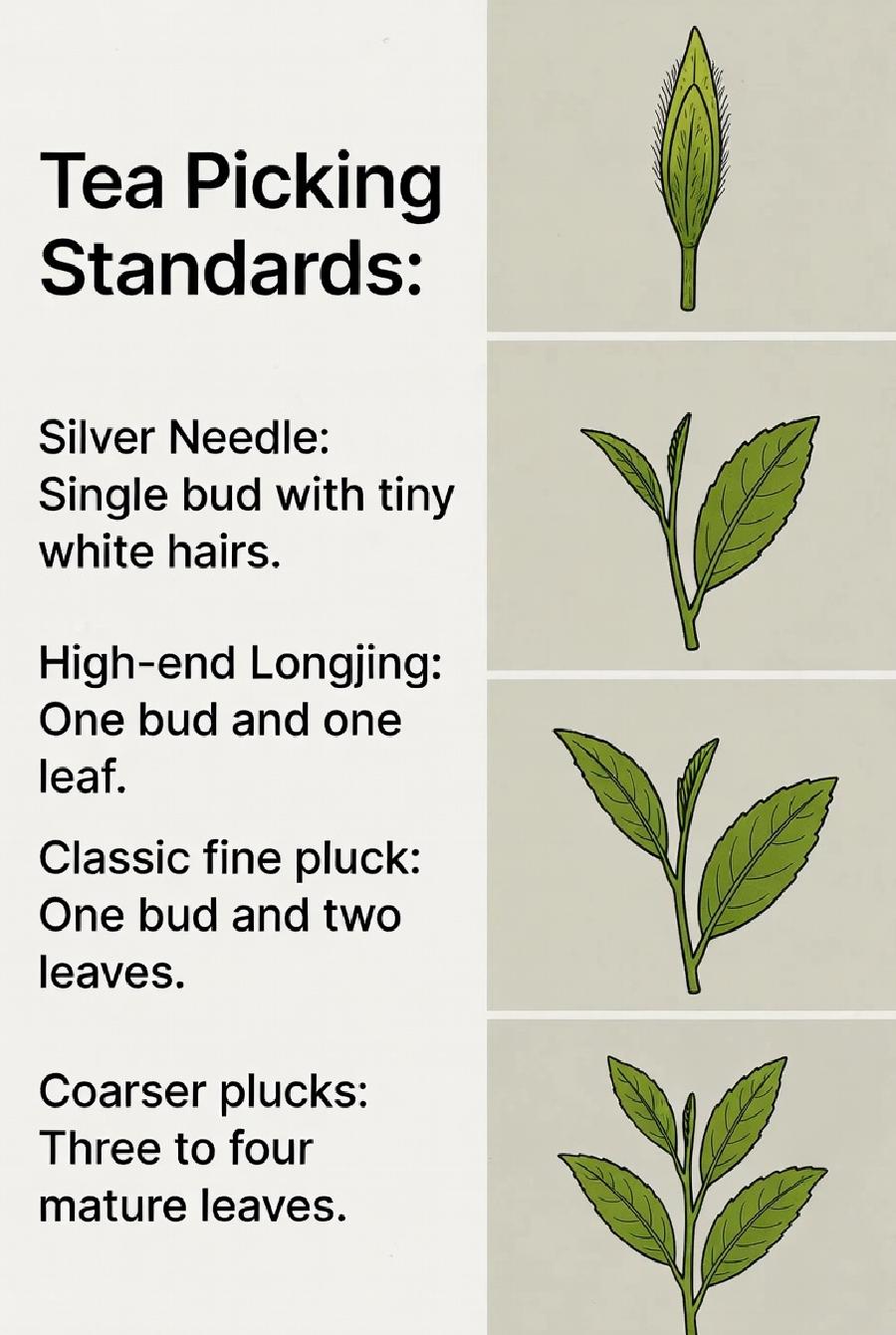

2. Anatomy: The Plucking Standard

When we talk about “parts” of the tea plant, we aren’t just grabbing handfuls of hedges. We are looking for the tenderest growth at the very tip of the branch.

- The Bud (Single Bud): The unopened leaf at the tip. It’s covered in tiny white hairs (trichomes). Teas made of only buds (like Silver Needle) are delicate, silky, and prized.

- One Bud, One Leaf: A balanced plucking standard often used for high-end Longjing (Dragon Well).

- One Bud, Two Leaves: The classic “fine” pluck. The bud provides sweetness, while the two leaves provide the body, aroma, and complexity.

- Coarser Plucks: Teas like Oolong or Pu-erh often use more mature leaves (3 to 4 leaves down) because they require more “material” to survive the intense oxidation and roasting processes.

3. Other Factors Affecting Grade

Beyond the date and the pluck, two other “invisible” factors can make or break a tea’s quality:

Hand-Picked vs. Machine-Cut

- Hand-Picked: High-grade tea is almost always hand-picked. This ensures only the perfect buds are selected without bruising the stems.

- Machine-Cut: Used for mass-market teas. It’s efficient but results in broken leaves and “yellow flakes” (old, bitter leaves), which lowers the grade significantly.

Weather on Harvest Day

A perfect “Ming-Qian” pluck can be ruined by a rainy day.

- Sunny Days: Ideal. The leaves are dry, and the chemistry inside the leaf is stable.

- Overcast/Rainy: Excess moisture on the leaves during harvest can lead to “dulling” the flavor or unwanted oxidation during transport to the factory.

Summary Table: How Harvest Affects Your Cup

| Feature | High Grade (Top Tier) | Standard Grade |

|---|---|---|

| Harvest Time | Pre-Qingming (Ming-Qian) | Post-Rain (After Guyu) |

| Pluck Type | Single Bud or 1 Bud/1 Leaf | 1 Bud/3 Leaves or Large Leaves |

| Method | Delicate Hand-Plucking | Machine or Rough Hand-Pick |

| Flavor | Sweet, Nutty, Delicate | Bold, Astringent, Grassy |